Recipes to Hold Dear in Your Hand

Cookbook zines render social media algorithms meaningless.

CREATOR (CREATIVE) RESISTANCE

In the new 2021 afterword “Do Zines Still Matter?” in the re-release of his 1997 book Notes From Underground: Zines & the Politics of Alternative Culture, Stephen Duncombe writes, “Zines have always been more than just words or images on paper: they are the embodiment of an ethic of creativity that argues that anyone can be a creator.” Duncombe was referring to the question of why people continue to make zines printed on paper, something you hold in your hands, when “computer-related communication” exists. If, with the internet one can reach millions of people, what does self-publishing, for example, a small scale cookbook or other food zine accomplish? If the question is whether zines and their paper still matter in a digital world, isn’t that materiality their biggest appeal?

Historically, zines have been an outlet for resistance (political or otherwise), culture-making from within instead of merely consuming mainstream cultural media, and myriad other do-it-yourself methods of expression and community. Akin to community cookbooks—often also self-published—food zines “disrupt food media by simply existing as a satellite or a moon, vaguely in the other’s orbit but not quite part of the same ecosystem,” writes historian N.A. Mansour in The Ephemeral Appeal of Indie Food Zines.

As a freelance, often self-published internet recipe writer who at one point thought she wanted to write a traditional cookbook, I’m especially interested in where short format cookbooks (as opposed to gargantuan books boasting of 100+ recipes) and food zines in general fit into cookbook cultural production. If with a diy publishing project one is resisting anything, might it be the endless frustrations that come from submitting ourselves to the whims of algorithms?

“We need zines, and it is revolutionary to realise that if you want something to exist, you can just… make it exist. Once you open that door, it remains unlocked.” - Gan Chin Lin, writer of the cooking zine Shelf Life

HAVE YOU CONNECTED WITH MY PERSONALITY?

Last year the New York Times reported that cookbook sales had declined 14.5% from 2022. To the rescue? TikTok stars, along with millions of loyal followers who have resuscitated the “sagging cookbook market.” This piece reminded me of an Eate Collective essay I’d recently read by Jacob Smith. In “The Overlooked Impact of Recipe Books on Social and Cultural Identities” Smith says, “[Cookbooks] are both historical texts which record food practices and availability, and important everyday texts that reflect and reproduce the socio-cultural milieu in which they are created by communicating present societal norms.”

Sixty second TikTok cooking videos translating to enormous cookbook author advances (in some cases, six figures and more) and sales is just a communication of the moment. In the past I, with my just over 4,500 Instagram followers, have been guilty of bemoaning this reality. In order to get a cookbook deal you need to have a built-in audience or platform of some kind because book publishing is a business that has to make money in a capitalistic world. I knew this, but didn’t want it to digest because that would’ve meant something I wanted wholeheartedly—a cookbook with recipes from my cottage bakery—was almost entirely out of my control. It makes no sense for a publisher to take a risk on a recipe writer without a platform, but zines remind me: Do it anyway; do it yourself.

The vibe—the photographs, the personality—in a TikTok star’s cookbook is an important aspect since their whole platform is based on aesthetics, while the recipes themselves may be of less importance. A publicist quoted in The New York Times admitted: “A recipe doesn’t need to be all that new or perfect,” she said. “It’s really just: Are they connecting with a personality?”

New York-based Jenn de la Vega, cook, writer and Editor at Large of Put A Egg On It echoes this in an email to me. “Since zines are made by individuals or collectives, you’ll find voices you otherwise would not encounter at a big box book store or from a major publisher. I love zines because they bypass bureaucracy.” de la Vega, who tells me she “really vibed with the mission of Egg, ‘the communal joys of eating with friends and family.’” The mainstream market for cookbooks puts the emphasis on aesthetics and metrics. Zines and self-publishing gives us an opportunity to do something about these frustrations, one that allows a focus instead on excellent writing and the recipes themselves.

“I loved the DIY nature of my college radio station and felt that same punk camaraderie in food zines.” - Jenn de la Vega, Editor at Large of Put A Egg On It

NEVER FOR MONEY, ALWAYS FOR LOVE

The inherent independence that comes with self-publishing your own recipe work and not relying on or waiting for the mainstrem, the instutitional to platform you is part of the appeal to myself and food zine writers. “I preferred the zine world over freelance writing for the freedom,” de la Vega tells me. “I wasn’t softened or edited ‘too hard’ for fear of brand safety. We could say what we were feeling without an online backlash. Other food zine makers were people I liked hanging out with: queer, creative, scrappy, and extremely collaborative. There was an openness with resources and time.”

This do-it-yourself approach to getting your work in the hands of people who can enjoy it is empowering, but not without its own limitations. When asked about the drawbacks of publishing indie work, de la Vega says, “Money. I had a full-time job in tech then, so I didn’t think about the labor cost I spent on the zine. Since we weren’t in the advertising machine, we didn’t have the capital to go bigger or to hire folks.”

The sentiment is shared by Gan Chin Lin, vegan recipe writer and creator of a recipe Patreon of the same name. “I would say the drawbacks are deeply personal to your goal with publishing indie. Certainly it’s the furthest thing from a quick fire moneymaking scheme.” Lin, who wrote Shelf Life as “a handful of recipes which retooled fragments of Singaporean food heritage/memory with elements of modernity”, says she was inpsired especially by vintage cookbooks “which were hyperfocused, bizarre, obtuse and impractical.”

A zine can be whatever you want it to be—a few pages of printer paper stapled together, or a more elaborate project printed on glossy paper with color images. It is work that you are unlikely to make a profit from, but as Duncombe reminds us zine’s inherent rejection of consumerism in Notes From Underground, “While other media are produced for money or prestige or public approval, zines are done—as Factsheet Five’s founding editor Mike Gunderloy is fond of pointing out—for love: love of expression, love of sharing, love of communication. And in protest against a culture and society that offers little reward for such acts of love, zines are also created out of rage.”

Gan Chin Lin, who says she first started drawing and writing as a child and was trying to rekindle a spirit for the DIY with Shelf Life writes, “Your profit will never truly match the sum cost of: developing recipes, shooting them, designing and writing the zine and processing all that material, liaising with printers, publishing, being your own publicity team, managing orders and payment, then processing the product to ship to various countries in various continents—it is physical, emotional, financial.”

Still, every one of the zine writers I spoke with shared the same thought with me, that despite there being little to no profit in zine-making, they urge other people who want to go this DIY route to just do it. Los Angeles-based Ej Bautista, writer of the digital and material Cook Club Zine #1 “Cut Your Own Fruit” shared with me that, “The factor that I am most grateful for about Cook Club is actually that I have stopped putting pressure on myself or others to create for the sake of consistency. That’s what has been great about publishing indie; I know I can make art as a hobby when I feel most capable and inspired.” It is empowering then to put a piece of material work out into the world—on your own terms, with your own words—one that can’t be traced or surveilled through social media metrics.

“It [Cook Club] started in 2020, as many passion projects had, so this ‘club’ was exclusively online on Instagram. In reality, though, I see Cook Club as more of a digital public library with a recipe archive.” - Ej Bautista, creator of Cook Club #1 “Cut Your Own Fruit”

RECIPES OF LOVE AND DEVOTION

My relationship with the virtual is metamorphosing. To write this piece I needed to delete Instagram off my phone. A compulsive choice, the only thought behind it was: this makes me feel bad; I instead want to feel good. Instagram needed to go from my immediate attention to the back burner. Let it safely simmer away without watching. Scrolling is a distraction and I needed to write. But what I really needed was to be without the app I at one time felt was necessary to someday write a cookbook, to keep my bakery and recipe work in the minds of everyone. (Don’t forget me!) DMs have made me too available to people. I say yes too much when my body is screaming NO. I’m just trying to get my bakery out there. “Out there”, as if it doesn’t already exist in a real life city with real life customers whose real life arms I place pink boxes of cake into each week.

But, if I’m not making Reels or even showing my face on my account all that much anymore, what chance do I have? I had to ask myself—if the numbers never came would I still want to do this work? My answer is another question: what else could I even do? A nine-to-five would be a death sentence to my emotional and spiritual interiority, and I know this because I’ve worked nine-to-fives. I’ve been dead.

When I knew I wanted to finally dedicate time to writing this internet recipe culture series, I had zero intention of pitching it to any food media. I was always going to self-publish, as the whole process of pitching to an editor has always felt demoralizing to me. This impatience, this insistence on using my own voice, my own resources has served me in this work I choose to do. Instead of hoping for mainstream validation that may never come and is out of our control anyway, those of us fed up with playing the numbers game in an increasingly demoralizing digital space can contribute to an alternative space, one rich with a cultural history of self-designated relevance.

I’m not sure I want to play the game anymore. I don’t even know if I still love to post (lol). My bakery allows me a certain connection in the irl that I really need, and maybe this is the end of At Heart as a strictly online bakery. I’m not sure when I’ll be back to posting on Instagram, if I’m just in one of my moods that will pass as soon as I publish this, or if this is a symptom of something deeper, something that I need to take my time in figuring out. I get enough bakery orders from my repeat customers and word of mouth, that posting constantly to Instagram (Don’t forget me!) feels less and less like a necessity. As I go through the metamorphosis, I’m focusing on work with roots in the material world, work one can hold dear in their hand.

Further reading and research:

Everything Cookbooks podcast episode #47: Self-Publishing Cookbooks with Nick Fauchald

Writing and Reading Zines as Resistance, by Devin Kate Pope featuring this banger from Charissa Lucille of Wasted Ink Zine Distro in Phoenix, AZ: “A powerful shift can happen when a higher number of folks are absorbing a higher rate of underground self-published works rather than mainstream voices and ideas.”

American Counterculture, Glimpsed Through Zines, by Hua Hsu

“If everyone’s a sellout now, like they say, but only some people are actually getting things sold, what we can expect, I believe, is a new wave of artists who decide not to play the game.” (On Creativity by Cydney Hayes)

Fantastic read! I always think about cookbooks that stand the test of time, like Claudia Roden or Julia Child. I see so many recent cookbook releases, with trending recipes, digital drawings and fashionable colours and fonts, knowing full well that in a year they will seem outdated. Originally and a creative authority seems to be the last thing that the industry is interested in.

Yes!!!!!!!!! I’m working on my first zine with my partner. Can’t wait to share it with our community here in Austin. We are probably also going to do a digital version.

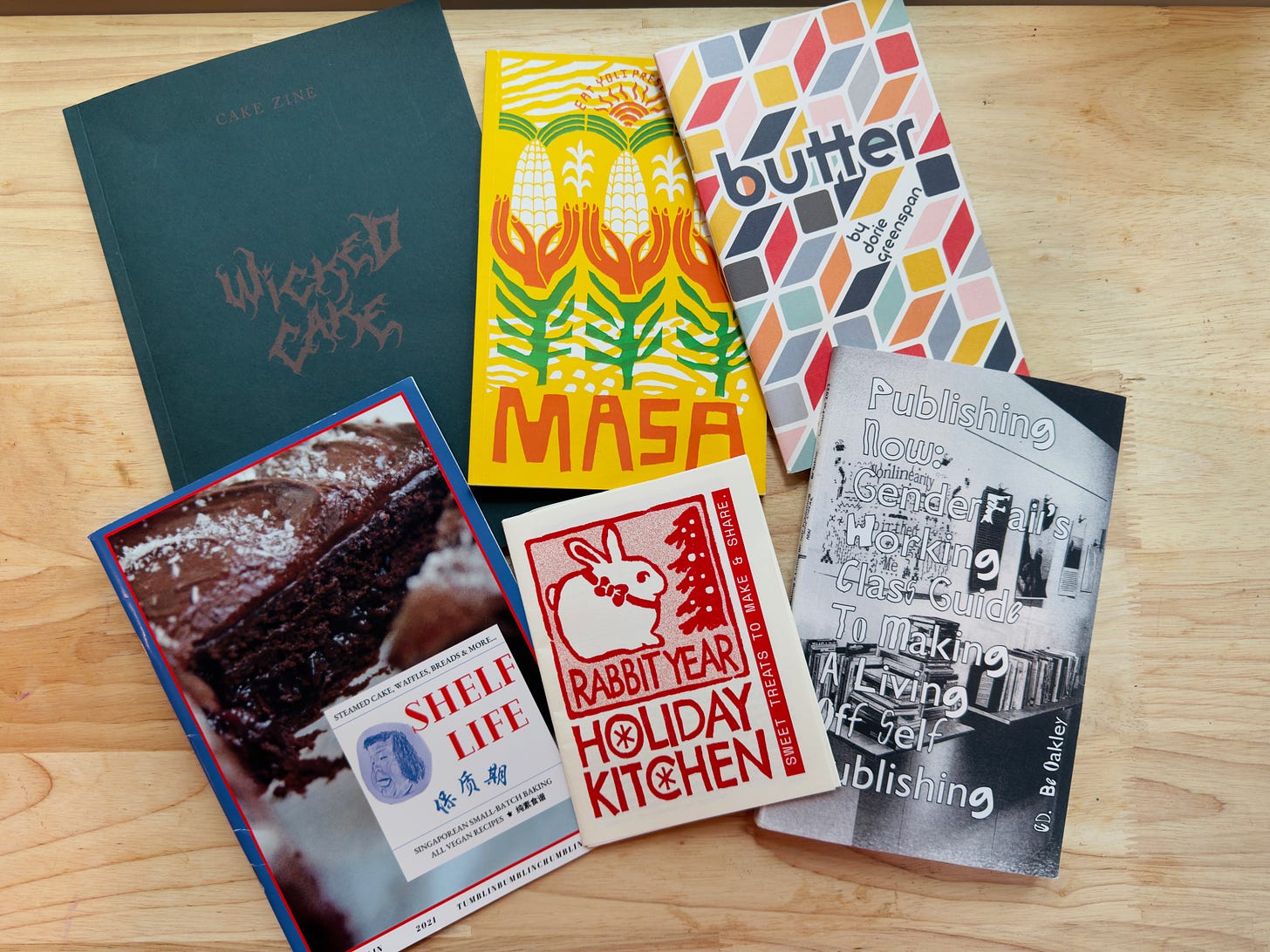

Thank you for writing this piece! I have been thinking a lot about zines and their role in the food writing and cookbook writing space the past couple of years. So happy to see so many new examples.